Think art history is mundane? Think again. These scandals rocked the art world and created widespread controversy that still causes contention today.

The last installment of a three-part series on major art scandals. Check out Part 1 here, and Part 2 here.

Battle Three: Marcel Duchamp v. What is art, anyway,

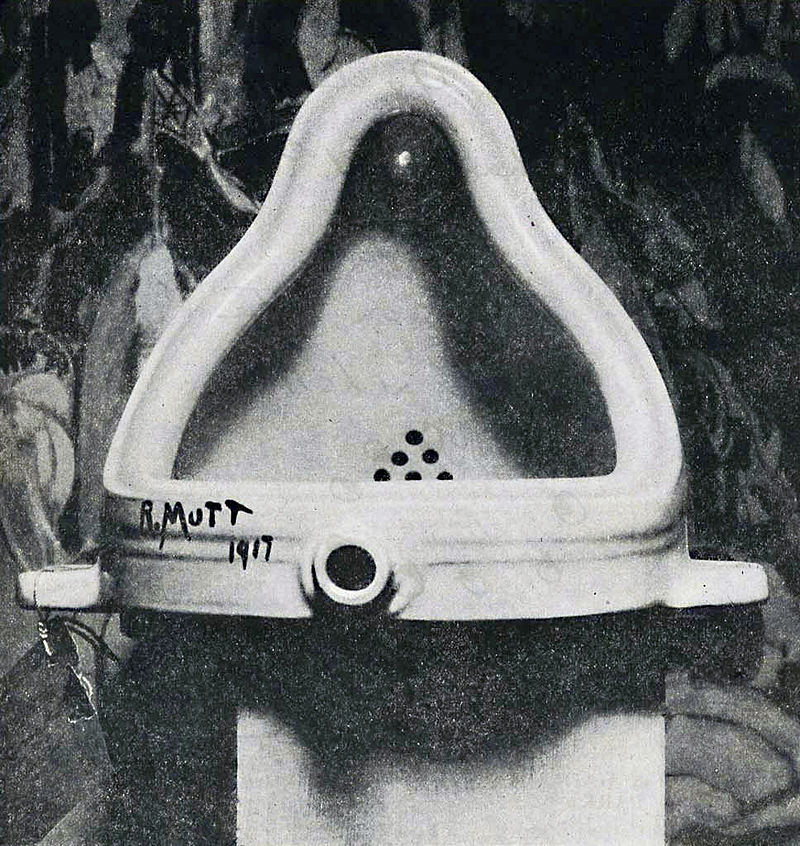

The Battleground: Fountain, by Marcel Duchamp… not the kind of fountain you were thinking of, is it?

The competitors:

Marcel Duchamp: Though he never chose to align with any sort of artistic movement, Duchamp’s work best fits as Dada Art, which About.com provides an easy definition of: “Dada was officially, not a movement, its artists not artists and its art not art.” OK, that admittedly makes little sense. Really, what Dada Art — and Marcel Duchamp — stood for was a constant sense of humor and a constant questioning of the boundaries of art. Duchamp became known for his readymades, a collection of various “ready-made” items that Duchamp would put his original spin on (see the signature in Fountain above). By removing these items from their traditional spaces and placing them alongside famous art, Duchamp hoped to provoke the question: what is art? What do these things represent beyond the physical realm they inhabit?

Marcel Duchamp: Though he never chose to align with any sort of artistic movement, Duchamp’s work best fits as Dada Art, which About.com provides an easy definition of: “Dada was officially, not a movement, its artists not artists and its art not art.” OK, that admittedly makes little sense. Really, what Dada Art — and Marcel Duchamp — stood for was a constant sense of humor and a constant questioning of the boundaries of art. Duchamp became known for his readymades, a collection of various “ready-made” items that Duchamp would put his original spin on (see the signature in Fountain above). By removing these items from their traditional spaces and placing them alongside famous art, Duchamp hoped to provoke the question: what is art? What do these things represent beyond the physical realm they inhabit?

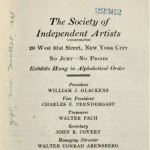

The Society of Independent Artists: founded in New York in 1916, the SIA displayed new, innovative and experimental artworks. Their goal was to democratize art: anyone could display their work in the SIA’s annual shows, as long as they paid the entry fee, and all art was displayed not thematically but alphabetically, with the first letter drawn from a hat. They truly were an edgy group of artists, which Duchamp – a member of the Board of Directors – intended to challenge.

The Society of Independent Artists: founded in New York in 1916, the SIA displayed new, innovative and experimental artworks. Their goal was to democratize art: anyone could display their work in the SIA’s annual shows, as long as they paid the entry fee, and all art was displayed not thematically but alphabetically, with the first letter drawn from a hat. They truly were an edgy group of artists, which Duchamp – a member of the Board of Directors – intended to challenge.

The history:

It’s one of the most famous stories in modern art history. The Telegraph writes:

Three men met for lunch in New York early in April 1917. They were the American painter Joseph Stella, Walter Arensberg, a wealthy collector later obsessed by the notion that Bacon wrote Shakespeare, and Marcel Duchamp. After a convivial and talkative meal, they made their way to the JL Mott Ironworks, a plumbing suppliers situated at 118 Fifth Avenue. Once there, Duchamp selected a “Bedfordshire” model porcelain urinal. On returning to his studio he turned it through 90 degrees, so that it rested on its back, signed it, “R. MUTT 1917”, and entitled this new work Fountain.

The scandal:

What did Duchamp do from there? Well, as a member of the Board of Directors of SIA, he knew they had ruled that every work submitted must be displayed, so of course, he submitted it under the name and fake address of Mr. Mutt. The work caused an outrage, with members of SIA calling it “vulgar” and a mere “bathroom appliance.”

By a narrow vote, the Board decided not to display Fountain, and in response, Duchamp and Arensberg stepped down immediately, and the story hit the news. A few months later, an anonymous declaration — most likely written by Duchamp — surfaced, including a picture of Fountain, pronounced:

“Whether Mr Mutt made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object. As for plumbing, that is absurd. The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.”

You can read more of the declaration here.

And the winner is:

Duchamp, by a long run. Critics have called it the most influential work of modern art. Certainly, Duchamp’s ability to provoke questions on why someone likes art, or what we consider to be art, have gone down in history and influenced basically all of modern art. Duchamp himself remains remembered by all for continually subverting artistic norms and expectations and adding humor and even mockery to the often too-serious world of art. He basically summed up this idea in the quote:

“People took modern art very seriously when it first reached America because they believed we took ourselves very seriously. A great deal of modern art is meant to be amusing.”

Unfortunately, you can’t see the original piece itself. The original was mysteriously misplaced after its veto by SIA. The picture above is the only known photograph of it. However, Duchamp allowed several replicas to be made in the 1950s, which can be seen at the Tate Modern, SF MOMA, the Met, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and more. Is there one in your area? Look here.

Marcel Duchamp is featured in the ADP lesson for fifth graders, “Cubism,” with his work Nude Descending.