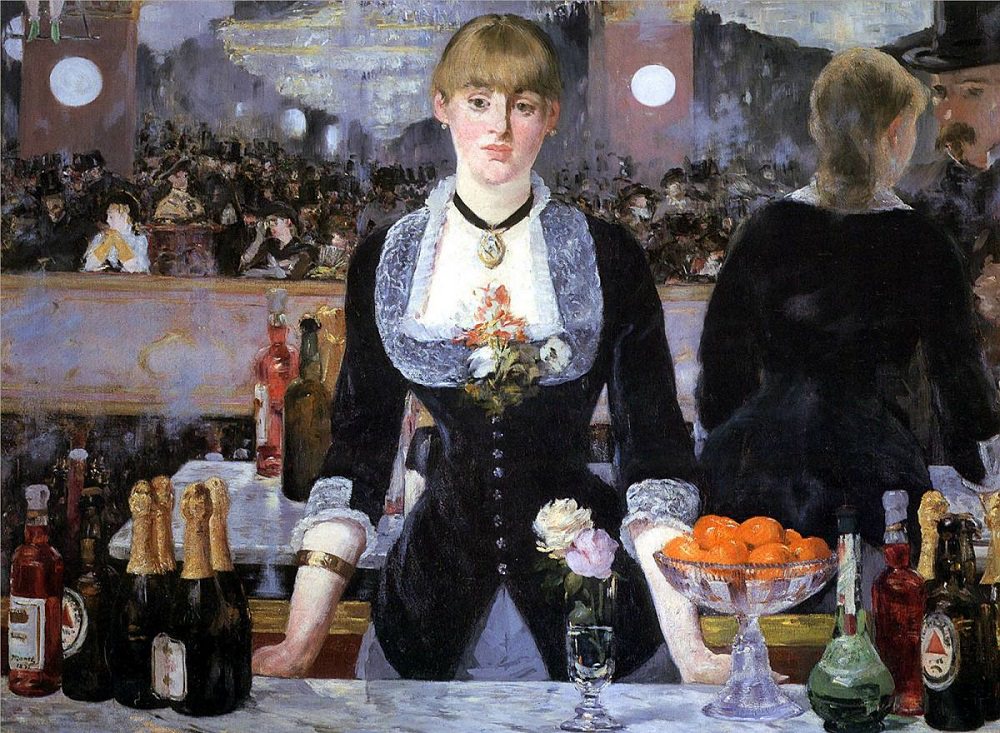

We haven’t gotten #fancy in a while, so today we’ve decided to bring it back with Edouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère!

Manet, better known for his realist paintings, is experimenting with Impressionist trends and subject matter in this 1882 painting. And he’s adapting the style quite well. The clearly visible brushstrokes make up the fashionable Folies-Bergère, a music hall frequented by the avant-garde, and the curiously day-dreamy barmaid. Manet gives a nod at the history of art by using the bar as a platform to exhibit his skills in still life painting by placing a bowl of oranges, a staple of Dutch seventeenth-century still life paintings, in the foreground.

But what is with this barmaid? She’s clearly spacing out big-time, and she doesn’t fiercely meet our eyes like the other strong female subjects of Manet’s earlier work (like Olympia). This may be the fact that Manet is truly trying to adapt to the ideas behind the subject matter of Impressionism as well. Impressionism was obsessed with the mechanics of sight and seeing, hence the visible brushstrokes and use of color contrasts (think of Monet’s Impression: Sunrise). The water isn’t actually orange and the people in the rowboat aren’t actually navy—it just looks that way because of the way the sun is rising and reflecting. And we get that because it’s how we see. The idea of looking and being looked at also factors into many Impressionist paintings as well. That’s why so many Impressionist paintings are of social settings like theaters, music halls, and cafes—the idea of going to see an event, but actually watching the people surrounding you as well was a big part of Impressionist painting.

In Bar at the Folies-Bergère, we get that social element. The crowd is reflected in the mirror, and the barmaid is the perfect person to watch them all. And she, with her jewelry, flowers, and fancy dress, is perhaps the perfect person to watch, if you’re a creepy male customer. But she’s not free to sit around and just take in the social scenery—she’s clearly weary and her mind is somewhere else. Other than that, she doesn’t really tell us a whole lot. This hints at the problems of later Impressionism. Manet showed up pretty late to the party, as Impressionism really began in the late 1860s, and a lot of his contemporaries’ paintings had already experimented with what he was doing. The subject is sacrificed in order to see—a weird paradox that ultimately contributed to Impressionism’s slow fade out.

But man, is the Folies-Bergère #fancy.