Back when I was still in college (a whopping 3 weeks ago), I remember several conversations I had with my art history professor. When covering the Impressionist painters and when talking about the scholarship surrounding Vermeer, she brought up a very important point. What does it mean to see, and what does it mean to look? Can you see without looking–or look without seeing? How does one–whether they’re an Impressionist painter or a twenty-first-century art history student considering graduate school–look deeper into the art of looking?

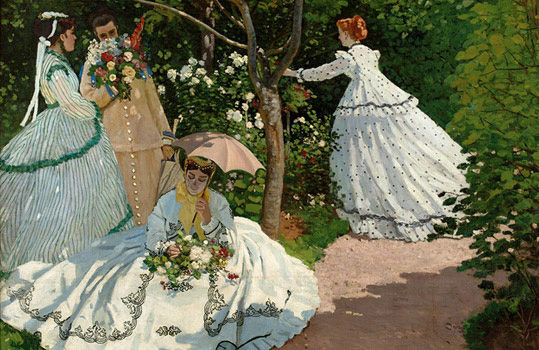

If you’re an Impressionist painter, you paint–you paint the first impression of what you see. You form your idea of how the painting is going to look by going outside (with your newfangled paint in metal tubes and your easel) and noticing how your eyes work. Does the seated woman in Claude Monet’s 1866 Women in the Garden really have a slightly discolored face? No, but the reflection of light from her white dress makes it look so. The Impressionists had tons of fun playing with the notions of how and what one sees, and were able to do that by noticing the details. Kind of like how art history students, according to my professor, need to be able to stop and look at the art–not only should they know the historical circumstances surrounding the painting, etc., but they ought to be able to sit and look at the painting for a long time, paying attention to the details and synthesizing what they already know with what they see.

Photo c/o frenchculture.org

In today’s society, we do a lot of looking. However, it’s rarely at one thing for an extended period of time. Even while sitting at a computer or lying around looking at our phones, we’re constantly switching between windows and screens. But we’re not moving around and (generally) not doing as much deep thinking–partly because of the nature of what work on a phone or computer would require us to do, and partly because there’s so much going on that we’re just trying to take it all in.

With so much attention to the visual but little actual interaction (i.e. how many photos do you see on Instagram vs. how many you actually stop, look at, and like), many people are now realizing that in some areas, kids are wildly understimulated. According to this Huffington Post article by Cris Rowan, the preeminence of technology that requires kids to stay physically sedentary while internalizing information at a fast pace reduces children’s imaginative faculties and decreases their ability to self-regulate and pay attention. While the article goes on to blame a number of behavioral disorders on technology (which it never backs up with scientific evidence), it does have a point: today’s kids are developing in a much more technologically-focused world than kids even ten or twenty years ago were. In addition to affecting kids’ waking lives, today’s overabundance of technology also affects their sleep habits and development, as this article from the team at Nestmaven details.

This isn’t necessarily all bad, but it is certainly affecting the way kids today learn to look at things, as my art history professor might have said. Which is why getting kids to really look at–and then create–some art is probably a good idea. Or why getting them into art media programs specially designed to stimulate creativity (kind of like us at the Art Docent Program!) might be something teachers and parents should consider, as it combines the digital literacy today’s kids already have with their own creativity. In addition to balancing kids’ informational intake (whether on a computer or in a classroom environment) and social and physical engagement (whether that be running around or interacting with friends or family, etc.), kids should also have the opportunity to exercise their creative muscles. If the visual arts are what stimulates kids, then by all means give them the opportunity to experiment in this field. Aside from shamelessly plugging our program, we really do think kids ought to have the opportunity to express themselves creatively in the medium they choose. The discipline that comes from having to not only plan on how to create a piece, but in following through and not giving up until the final product is completed is a valuable skill for kids to gain–no matter what they choose to do in the future. Art programs and art-related media also encourage kids to stay focused on one thing for an extended period of time.

So how does this circle back to the looking versus seeing debate? Immersing children in art and media-related programs (such as the Art Docent Program) encourages them to pay attention to the details–to really notice, to really look. This practice of looking applies beyond art and art history. What does it mean to really notice the world around you–to look at the details as well as see them? That is the question. And it starts with balancing screen time with plenty of physical and mental input.

Want more on how technology affects kids’ development and sleep? Check out this Huffington Post article, as well as this article from Nestmaven for ways you can help your child develop healthy digital habits.

Check out more about us and our curriculum here! And don’t forget to follow us on Facebook to keep up with what’s new!