This week in Artist Spotlight, we take a look not at an artist’s lesser-known work, but at a lesser-known artist herself that you should really get to know.

Have you seen this woman before? You may not realize it, but you probably have.

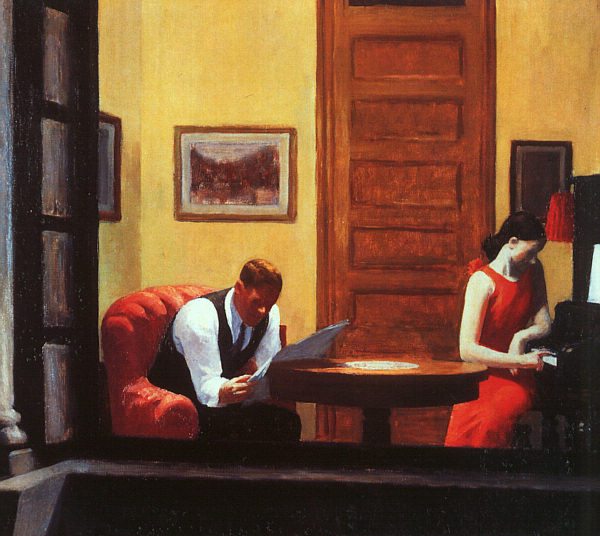

Here she is again, in Hopper’s “Room in New York.”

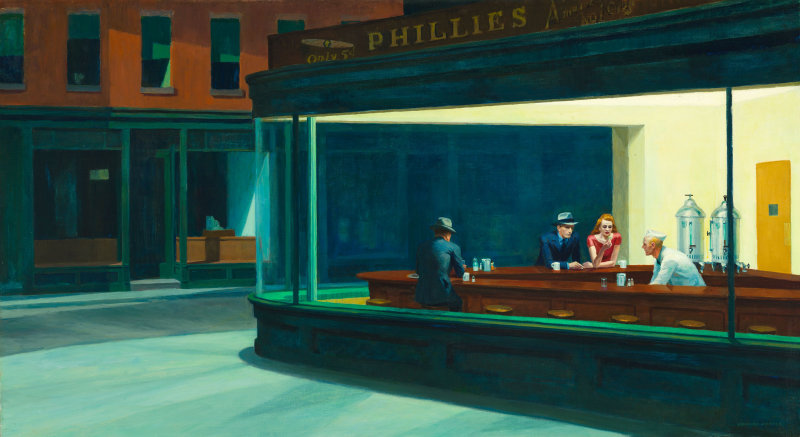

And she pops up again, in Hopper’s most famous painting, “Nighthawks.”

Yes, it is the same woman in every picture. This woman was Edward Hopper’s only model. But she was way more than just a pretty woman posing for paintings.

Meet Jo Hopper, Edward Hopper’s wife and inspiration. Here’s what you should know.

1. No one had high expectations for her.

Born in Manhattan in 1883 to a low-class couple that had already lost one child, Josephine Nivison went to college to study art and hopefully become a teacher, and even finding herself homeless and broke for a short time, she wound up teaching and spending summers at East Coast artist colonies.

2. She was more successful than Edward when they first married, with her work compared to John Singer Sargent and Georgia O’Keefe.

When she met Ed Hopper in art school, she didn’t pay him much attention. His artwork, in fact, didn’t receive much attention either for several years to come. When they re-met at a Massachusetts art colony in 1923, however, her influence on him was astounding. The two married just a year later, and she quickly became his only model, and his muse as well. By the early 1900s, according to The Guardian, her work “had been shown alongside that of Modigliani and Picasso, Maurice Prendergast and Man Ray.” With her drawings featured in several newspapers, she quickly became an up-and-coming artist.

3. You won’t find her work online, or in many museums: after her marriage, her career tanked.

Shortly after her marriage, Edward released his famous painting, Nighthawks. From there, his career began to soar. Jo’s career, on the other hand, began to plummet, receiving poor reviews at art shows. Why?

Some blame Edward himself: the facts show their marriage was not a happy one. Though the pair stayed married until Edward’s death in 1967, they both kept detailed journals full of sketches and writings that air all the dirty laundry between the couple. Did he suppress her talent? Well, their styles could not be more different: his was narrative, heavy, oil-based. Hers were grounded, but almost fauvist in color. He did not allow her to drive, so they ended up painting many of the same subjects.

COURTESY ARTHAYER R. SANBORN HOPPER COLLECTION TRUST

Ultimately, her work suffered as she grew simultaneously resentful of her husband’s success. Their passionate but tumultuous marriage gave her much to complain about, and their secluded lifestyle caused her to vent in her journal entries, complaining about his ego and lack of concern for her happiness.

4. She named her husband’s most famous painting, Nighthawks.

Despite her marital problems, Jo also remained completely in love with Edward and devoted to his art, writing:

“It’s such blessedness that Edward and I have each other. Surely I’ll be allowed to go when he does.”

How did she show her love to him? She helped her husband create sketches for his painting prep and took detailed notes on their composition. She was his only model. She kept all his records and even wrote his correspondences for him. And she named most of his paintings, as shown by these notes of hers on Nighthawks:

Very good looking blond boy in white (coat, cap) inside counter. Girl in red blouse, brown hair eating sandwich. Man night hawk (beak) in dark suit, steel grey hat, black band, blue shirt (clean) holding cigarette. Other figure dark sinister back—at left.

For more info on Josephine Hopper, check out this article from The Guardian. Edward Hopper’s work is featured in three ADP lessons.