For much of the history of western art, what is considered a “good” painting was judged by how well a painting conveyed a visual narrative—that is, how well a painting told a story. From just before the Renaissance onwards, the implicit hierarchy for what would

make a painting “good” was as follows—history paintings (paintings such as Bible stories, classical myths, or famous historical events) were considered the most intriguing and challenging for an artist to paint, followed by genre scenes (scenes of everyday life), portraits, landscapes, and finally, still life paintings. This unconscious hierarchy into which “good” art was structured persisted until the mid-1800s, when many artists began to question not only the traditional hierarchy, but many of the typical conventions in the history of art as well.

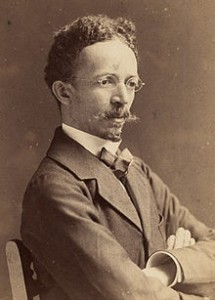

Henry Ossawa Tanner was born in 1859 in Pittsburgh, around the same time as the realist movement in Europe was in full swing. As he grew up, however, Tanner’s artistic talents weren’t exactly appreciated, as he was African-American. Despite the racism he

frequently experienced, he enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1879, where he became more intrigued by the questions about the history of art that many artists were tossing around. However, many critics and viewers were more interested about judging the color of Tanner’s skin rather than his artistic skill. In 1891, Tanner had had enough. He left America for Paris, where his artistic talents would be more fully appreciated. Apart from short visits home, he did not return to America.

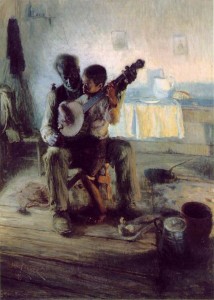

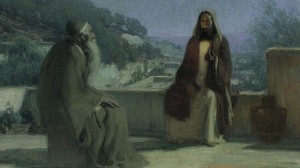

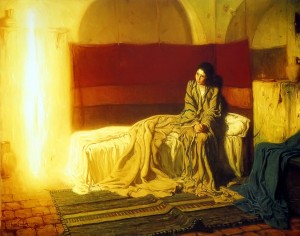

Tanner’s work is varied—he doesn’t paint exclusively in one genre. His work, influenced by realism and Impressionism, doesn’t fit nicely into one category—his career was long and fruitful, and he adapted to differing styles well. His most famous work is 1893’s “The Banjo Lesson,” a painting reflecting African-American tradition and criticizing stereotypes while utilizing visual cues used by both realists and Impressionists (read more here). Interestingly, while Tanner’s best work is considered “The Banjo Lesson,” a genre scene, the least-known of his paintings are his Biblical series. Tanner’s Biblical paintings are a Realist take on some of the most popular scenes in the history of art. His choice to base the human subjects of his paintings, including Jesus, on non-white Middle Eastern models and place them in the humble settings he saw on a trip to Palestine shows Tanner’s commitment to realism and his hopes to “preach” a truly inclusive and naturalistic Gospel “with [his] brush.”

I find it interesting that Tanner’s Biblical paintings, which would have been all the rage a hundred

years earlier, aren’t focused on today. Why is a historically accurate Middle Eastern Jesus or an Annunciation without a human-like angel so strange for viewers, even today? Probably because the old hierarchy isn’t the only art historical convention that’s stuck around—we have five hundred years’ worth of paintings of idealized, European human figures that we’ve been told are the gold standard. Anything else is deviant, or grouped with abstract or nonrepresentational art.

So let’s give Tanner a standing ovation for attempting to reify and strip away our implicit artistic prejudices. This guy was way ahead of his time. Or perhaps, Tanner’s works came at just the right time—except they never got the attention they deserved until now.

Check out PBS’ bio on Tanner for more on his life story and genre paintings.

Interested in Tanner’s biblical work? Check out Christianity Today’s artist profile.