In this series, we take a look at how certain seminal and lesser-known artworks have become symbols of social action. Check out Part 1 on Picasso’s masterpiece Guernica here and Part 2 on J.M. Turner’s The Slave Ship here.

Born with the name Howard Blashki in New York City in 1901, the artist who took on the name Philip Evergood was truly a jack of all trades: from sculpting to etching to painting, he did it all, and more! After talking all night with a group of homeless men he found on the street, Evergood was inspired to create Spring. With several paintings depicting and attacking the rampant poverty in America at the time, Spring falls right in line with his other works.

It started with a return home.

At the age of nine, Evergood’s family moved to England. After years of studying artists like El Greco and Bruegel in England, he returned to his home in NYC and faced constant poverty. Disheartened by the failure of the government or any charities to come up with real solutions to the problems around him, he took action. He became a local champion of artist and labor rights as president of the New York Artists Union, which staged demonstrations and created petitions to fight for freedom of expression and better wages for artists. He received regular work from the Works Progress Administration and quickly became a rising name along with Joe Jones and Ben Shahn in the Social Realism branch of art, which aimed to draw real attention to the everyday lives and problems of those in poverty rather than romanticize the lives of the working class or focus on the frivolous activities of the upper class.

One night, he found himself walking by a group of homeless men and struck up conversation with them — and ended up talking with them all night. His conversations with them directly inspired the composition of Spring.

In an 1968 interview from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, Evergood describes the scene in his own words:

“The frame shop is on the street, that same street. Christopher Street. And what more can I say about that. I was terribly impressed by these men without any shelter at all sitting huddled around a fire of broken orange crates that they had picked up on a pier right nearby, and just sitting there huddled in the cold with snow on the ground all around them… Well, that particular night was a milestone in my life. I was terribly upset and depressed by their poverty. And I got up from the fire and walked home to 49 Seventh Avenue where we were living at the time and got a drawing board and a lot of paper and walked back and started to draw. Some of the best drawings that I ever made were done that night… Because the material was there. Their faces. The characteristics of their different races and lives were all in their faces. They had funny names. They called each other not by he name of John or Jack but names like “Terrapin” and “Geetchie.” For instance, Terrapin was called by that name because he had killed and eaten terrapins down South. And so on… Later on I walked to a package store and bought a bottle of gin and warmed them up a bit with some gin. And went on all night drawing until dawn. I felt that was a milestone in my life.”

And the rest was history.

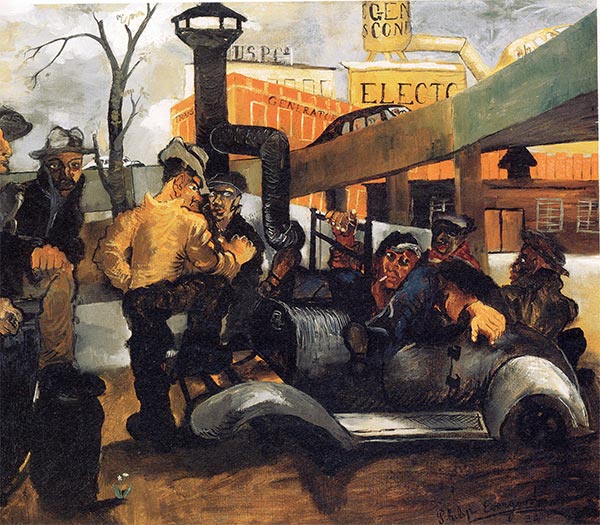

Evergood was no stranger to contention when it came to his artwork. Though he continued to receive regular patronage from the WPA, his art skewered the rich and angered many upper-class art critics. During the Depression, which had no shortage of poverty, the anger of the poor and the lack of caring from the rich became a main subject of his. Influenced by Bruegel’s focus on the lives of peasants and El Greco’s and Goya‘s embrace of the grotesque, Evergood became known for his crude and awkward depictions of people. Though certainly a Realist in showing the true problems of the poor, his paintings often seem not too realistic: these people are not comfortable and are not pleasant, but they do exist, he seems to say. Furthermore, his symbolism is flagrantly obvious, just how he wants it to be. He wants everyone to see these men gathered around a car without wheels and know the bigger message: these men are immobile. They have no opportunities to escape poverty. They have no way out.

More than any other artist of his time, Evergood championed art as a form of protest, and this may be his most lasting legacy. In his own words:

“Well, I think of anybody living today in America I have painted more social protest paintings than anyone else. I may be wrong. Because Jack Levine has done his share. And Ben Shahn certainly has, too. But I have devoted nine-tenths of my life to painting really social protest paintings, such as American Tragedy, the battle between the company police at the Republic Steel works in Gary, Indiana – you remember, when so many of the workers and their wives were shot down. I think I painted as many of that kind of violent statements of social protest as anybody else.

“If you paint a picture of an old man, a beautiful old man with a beard and tired eyes you’re painting something social. Actually if you paint a group of country folk having a feast like Breughel did it’s social painting, too. But then when you get down to paintings like The Massacre of the Innocents by Breughel when Holland was occupied by the Spanish and you have people smashing doors down and bringing out infants and cutting them in half with swords then you’re doing a very brave kind of social statement. That’s real protest.”

Philip Evergood’s Sunny Side of the Street is featured in the Art Docent Program lesson for first grade, “People at Play.”